Privacy in Location Based Services - Part 1 06 May 2017

In the mid 2000s (around 2006-2008) people started being concerned with their location privacy, so there was a boom of research papers coming out on this subject. Incresingly many people started having access to mobile communication devices (mobile phones, PDAs) and those devices had positioning capabilities (GPS, location). So the fear that your location data is public and people can find out your shopping habits, schedule, health issues and so on become real. This is still a threat today. But what this post (part one of two series) is trying to do is to present and discuss some of the solutions used to mitigate the privacy risks presented by the presence of a location based service in a mobile device. Most of those things are outdated nowadays, the state of the art in privacy is differential privacy, but it’s still interesting to know the long way privacy has come and is especially interesting to me since I am a security/privacy person. So take this as a personal project about the study of LBS privacy methods and it’s early days.

The subject will be presented in two blog posts, the first one presenting general information about location based services, what are they, what privacy risks they present, concepts for hiding location based information and attack models. The second part will present three methods for mitigating privacy issues in Location Based Services (LBS) and the vulnerabilities this models present.

What are Location Based Services?

In the past location based services where limited to traffic signs, now there’s a plethora of services and ways in which you can find out where you are (using your phone GPS, Google Maps, Mapquest etc.). Users can ask locatioon-dependent queries, such as “find the nearest gas station” at any time, but those queries may disclose sensitive information about individuals, like health conditions, lifestyle habits, political and religious affiliations, or it may result in unsolicited advertisement (LBS advertisement: send E-coupons to all customer in 5 miles radius of my store, aka spam). So if there are so many drawbacks why are we still using LBS? LBS rely on the implicit assumption that users agree on revealing their private user locations. They also trade their services with privacy - if an user wants to keep their location private they have to turn off their location-detection device and unsubscribe temporarly from the service. So, you want to be able to use LBS without totally compromising your privacy.

So, the solution is to find a trade off such that LBS information can still be used without being overly exposed. In a previous post we talked about k-anonymity, that will be relevant here as well soon. Privacy is not protected by replacing the real user identity with a fake one (a pseudonym), because in order to process location-dependent queries the LBS needs the exact location of the querying user. An attacker which might be the LBS itself, can iner the identity of the query source by associating the location with a particular individual. Most of the initial solutions for LBS privacy addopted the k-anonymity principle: a query is considered private if the probability of identifying the querying user does not exceed 1/k, where k is an user specified anonymity requirement. We will see later why this model offers weak privacy.

What is special about location privacy?

There are a few differences between location privacy and database privacy. We only talked about database privacy in the context of the k-anonymity in a previous post, but having that in mind we can highlight a few differences between the two:

- The goal of location privacy is to keep privacy of data that is not stored yet (received location data), on the other hand the goad of database privacy is to keep private the stored data (medical records, shopping habits on Amazon)

- In location privacy the queries need to be private (location-based queries), in databases privacy we don’t have that restriction, queries being explicit (SQL queries for patient’s records)

- Location privacy should be able to tolerate the high frequency of location updates (most of the time you will not have stationary users, they move around so your privacy model has to take into consideration that), the database privacy is applicable only to the current snapshot of the table

- And one of the most important aspects of location based privacy is that privacy requirments are personalized to each individual user, unlike in database privacy where the privacy requirments are the same for the whole set of data.

Concepts for hiding location information

Before we can move on there are a couple of concepts that are specific to location based privacy preserving and that we need to know.

Location perturbation

Is one of the simplest and weakest concepts. The user location is represented with a wrong value, the privacy is achieved from the fact that the reported location is false. The accuracy and the amount of privacy mainly depends on how far the reported location form the exact location.

Spatial cloaking

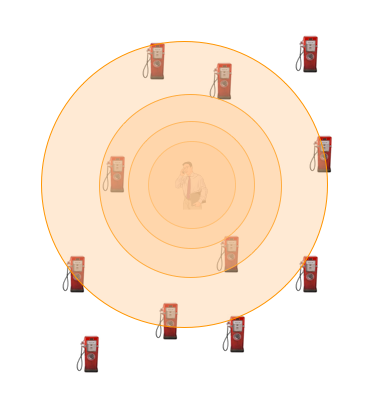

This technique is known as location cloaking, spatial blurring or location obfuscation, and the user location is represented as a region that contains the exact user location. An adversary knows that the user is located in the cloaked region, but has no clue where the user is exactly located. The area of the cloacked region achieves a trade-off between the user privacy and the user service.

Spatio-temporal cloaking

In adition to spatial cloaking the user information can be delayed a while to cloak the temporal dimension. Temporal cloaking could tolerate to ask about stationary objects (for example hospitals, gas stations, landmarks), but it is challenging to support moving objects (for example where is the nearest police car).

k-anonymity

The concept is the same as in databases privacy. The cloaked region contains at least k users and the user that asks the query is indistinguishable among other k users. The cloaked area largely depends on the surrounding evironment. For example, a value of k=100 may result in a very small are if the user is on a stadium but a huge area if he is in the desert.

Query types

LBS privacy has a series of specific queries that need to be answered:

- Private Queries over Public Data (for example: “what is my nearest gas station?”, the user location is private while the object of interest is public)

- Public Queries over Private Data (for example: “how many cars are in the downtown area?”, the query location is public while the objects of interest are private)

- Private Queries over Private Data (for example: “where is my nearest friend?”, both the query location and the object of interest are private)

Those query types map on users’ modes of privacy. When an user wants to hide their location information and their query information we have user location privacy. When an user doesn’t mind to disclose or is obligated to disclose their location but want to keep their query private we have user query privacy. Finally, when an user doesn’t mind to disclose a few locations but they don’t want an attacker to be able to link those locations as a trajectory we have trajectory privacy.

The location anonymization process - aka achieving the desired degree of privacy in LBS - needs to be accurate (the anonymization process should satisfy and be as close as possible to the user requirements), needs to not let an adversary to infer any information about the exact user location from the reported location, needs to be efficient (calculating the anonymized location should be computationally efficient and scalable), and flexible (each user has the ability to change their privacy requirments at any time).

System architecture for location privacy

To preserve privacy there are a few well know architecture models that have been deployed:

- client-server architecture where users communicated directly with the sever to do the anonymization process. Possibly employing an offline phase with a trusted entity

- third-trusted party architecture where a centralized trusted entity is responsible for gathering information and providing the required privacy for each user

- peer-to-peer cooperative architecture where users collaborate with each other without the interleaving of a centralized entity to provide customized privacy for each single user

All of those architecture models have different implementations that we are going to talk more about in the second part of this post.

Privacy Attack Models

An adversary may attack the privacy of an user in a few ways. The most obvious one is if an adversary manages to get hold of users’ location information, then the adversary may be able to link the users to their queries. How do you get hold of users’ location? The location might be public, for example employees are in their cubes during daytime hours. Or just hire someone to monitor the user location. The adversary may also try to link data from several consecutive location instances that use the same pseudonym, or it might monitor unusual continuous queries linking them with the user. Doing all this monitoring an attacker might have a good chance to get the user’s identity by using one of the following attack models.

Location distribution attack

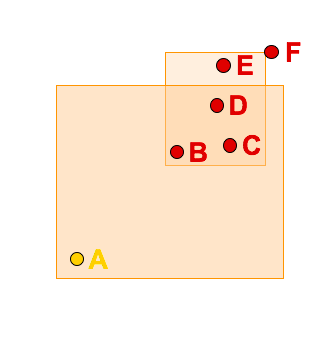

Location distribution attack takes place when:

- user locations are known

- some users have outlier locations

- the employed spatial cloaking algorithm tends to generate minimum areas

Looking at the example above, given a cloaked spatial region covering a sparse area (user A) and a partial dense area (users B, C, and D), an adversary can easily figure out that the query issuer is an outlier.

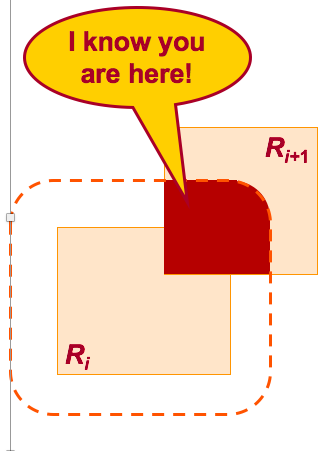

Maximum movement boundary attack

Maximum movement boundary attack takes place when:

- continuous location updates or continuous queries are considered

- the same pseudonym is used for two consecutive updates

- 5he maximum possible speed is known

The maximum speed is used to get a maximum movement boundary (MBB). The user is located at the intersection of MBB with the new cloaked region as seen in the below image.

Example of k-anonymity LBS privacy fail

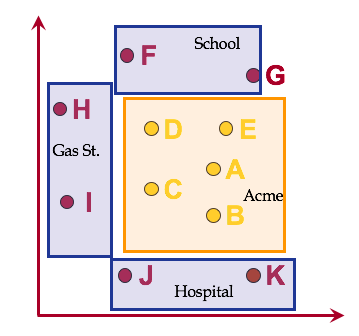

A group privacy violation can be illustrated by the following example. Acme is an insurance company with a large client list; the list is a valuable business asset and must be kept secret. Acme’s employees visit frequently their clients. To plan their trip, they use an LBS (e.g., Google maps) which suggests the fastest routes; due to varying traffic conditions the routes may change over time. Obviously, if the LBS is malicious, it can reconstruct with high probability the entire client list, by observing frequent queries that originate at Acme. To avoid this, queries are issued through an Anonymizer, which implements Spatial k-anonymity. The Anonymizer attempts to generate a small Anonymizer Spatial Region (ASR). Assuming k = 5 the ASR is the gray rectangle that contains {A, B, C, D, E}. Unfortunately, the ASR contains only Acme’s employees; therefore, the malicious LBS is sure that the query originated at Acme.

This example demonstrates that although k-anonymity is satisfied, the group privacy is violated.

Conclusion

In the next post of the series we will be talking about different privacy models in the context of LBS and their vulnerabilities.