A primer on differential privacy ACM XRDS 14 Apr 2018

I have started recently collaborating with the ACM XRDS magazine and my first article is out. It’s a gentle introduction to differential privacy and you can read it here.

Differential Privacy: an introduction in Python

Abstract: A short introduction to the differential privacy concept and a running example of the application of a differently private algorithm to a data set

Motivation and background

Privacy and security in general have always been a second thought to developers and software engineers, develop the product and then add security has been the way most companies think about it. But in the past couple of years there has been an awakening when it comes to privacy protection. This awakening comes in the light that even though average users have gotten used to the idea that they are sending a lot of personal information to various services they are still very uncomfortable about it. We rely on digital services for payments, transportation, navigation, shopping, health, and much more. So being uncomfortable that this amount of data is being collected and then used to market to us makes sense. But at the same time all the collected data represents a huge opportunity for research in multiple areas: improve transportation network, reduce crime rates, cure diseases, only if it will be made available to the right researchers and scientists. Unfortunately, sometimes even well-meaning data collection can go bad. For example, in the late 2000, Netflix ran a competition for improving their movie recommendation algorithm based on an “anonymized” sample of the data they have collected. Sadly, the anonymization they performed on the data set was insufficient, since Narayanan and Shmatikov[1] were able to re-identify specific users by cross referencing the Netflix data set with IMDB data base and identify the political affiliation of those users. The idea behind the anonymization technique, a version of which was used in the Netflix data set as well, is to eliminate the personal identifiers from the released data. Unfortunately, as it has been proved, if you remove the top 100 movies that we all have watched, you are left with a list of movies that is pretty unique to each of us. That is true not only for movies, but also for books, shopping lists, and pretty much anything. It’s clear that just anonymizing the data was not enough. Differential privacy (Dwork, et. al. 2006)[2] is a paradigm shift. The anonymization techniques and the improvements made on top of them were all properties of the data, so they were vulnerable different attacks, like cross referencing to another database, and they had no mathematical guarantee. Differential privacy moved away from privacy as a property of a data set. Instead, privacy is a property of a mechanism that produces a private result.

What is differential privacy

Differential privacy guarantees that an attacker can learn virtually nothing more about an individual than they would learn if that person’s record would not be part of the dataset. This means that if you are going to participate in a survey that asks you if you vaccinate or not your children, the result of the survey would be actually unchanged with or without your participation. Let’s say that you are not vaccinating your children, and you are participating in the survey. Then an analyst that looks at the data concludes that children that are not vaccinated present a higher risk of getting and transmitting diseases, so your health insures company which is the one that paid for the survey is going to use that information to raise your premiums – they know you are not vaccinating your children. In this case the privacy of the user was not broken. The result of the survey would have been the same even if you would have not participated in the survey. So, individuals have no incentive not to participate in a dataset, because the analysts would draw the same conclusion from that dataset no matter if the individual included itself or not. The sensitive personal information of individual users is almost irrelevant in the output of the system, so their privacy is not violated.

Mathematical background

The previous definition of differential privacy has an important part. An analyst can learn “virtually nothing more about an individual”, which means that the change in belief about an individual is restricted to a small change controlled by a parameter ε, that sets the bound on the change in probability of any outcome. A small value for ε (0.1 – 1) means that very little can change in the believes about any individual. A high value for ε (e.g. 50) means that the believes can change a lot. We prefer small values, so that the privacy of the individual can be preserved.

A formal definition of differential privacy is: an algorithm A is ε-differentially private if and only if:

PR[A(D)= x]≤ e*PR[A(D’)= x]

for all x and for all pairs of datasets D, D’. Where D’ is D with any one record missing. This definition only makes sense for randomized algorithms. An algorithm that only gives deterministic output is not suitable for differential privacy.

Running example – survey

Going back to the previous example of a health insurance company wanting to know if their clients are vaccinating their kids we can run a practical example to see exactly how does differential privacy work and why does it work.

Imagine that you are the researcher that is going to run this survey. You want to make sure that you keep your respondents’ privacy but you also want to get statistical relevant information from the survey. To be able to run your survey and preserve privacy you are going to give each respondent a survey and a coin to flip. When they get to the question about vaccinating their children they are instructed to flip the coin: if it comes up heads, they answer correctly, if it comes up tails, then they flip the coin again and answer “yes” if it comes up heads, and “no” if it comes up tails, with no regard to the truth of their behavior. The survey will contain a multitude of questions, not just about vaccinations, but this is the information we want to protect.

With this mechanism is pretty easy to see that the respondents’ individual privacy is going to be protected. At the same time, you are going to be able to get a general idea about the rate of vaccinations amongst the health insurance company clients (we subtract out the estimated number of “yes” answers from the total “yes” answers of the survey).

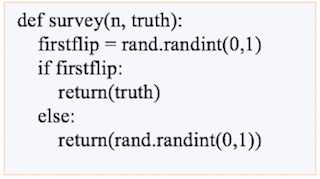

The procedure for our differentially private mechanism can be seen below. It will return either an accurate or a random answer.

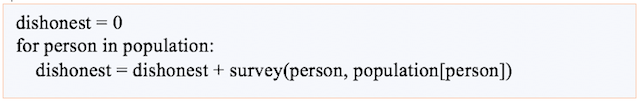

We apply this differentially private mechanism to our population. In this case is going to be an array of 2000 people, in which 25% of them are not vaccinating their kids. To make this easy we will consider the first 500 people in the array as those who do not vaccinate their children, and the rest as those who are.

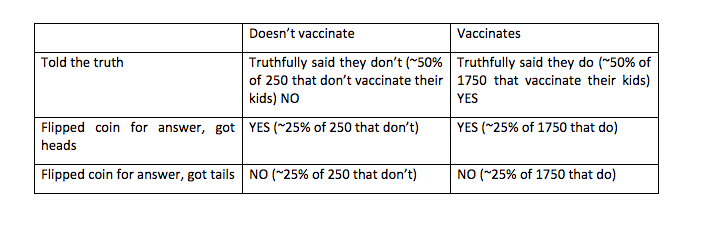

So what does this mean for us? Applying the differentially private mechanism from above to the survey gives us six categories of answers. The breakdown of the number of people in each category is below.

Aggregating the answers we are getting from the survey and plotting them as a histogram is going to give us the histogram below.

From the histogram we can gather that our differentially private algorithm for collecting survey data produces a result that is centered around the real number of 500 people (Value/2) that are not vaccinating their children.

Laplace mechanism – how to apply differential privacy with it

But of course, in real world we are not going to conduct surveys by offering our respondents a coin to flip for every question that we consider it has sensitive information. We are going to collect the data as it is from our respondents and then use a differentially private mechanism for data release.

We have established that differentially private algorithms are randomized algorithms (no deterministic answer) that add noise at key points within the algorithm. One of the simplest algorithms is the Laplace mechanism. Using the Laplace mechanism we can post-process results of aggregate queries (e.g. counts, sums, means – exactly what our survey was measuring) and make them differentially private. What the Laplace mechanism does it adds random noise sampled from the Laplace distribution to the real values of our survey. We could fit the Laplace distribution to our data and see exactly what this would mean. The result is seen below where we have applied the Laplace distribution to the histogram graph from before.

But why would this algorithm be differentially private? Having the dataset from our vaccine survey we can look at it from the viewpoint of an attacker Eve. She wants to know how many of the people in our survey are not vaccinating their kids. In our case there are 500 of them. But, by using this mechanism or the Laplace mechanism we can see that the answer to this query can vary from as low as 320 to as high as 640 respondents, with different probabilities. The values closer to the center of the Laplace distribution have a higher probability of being returned as answers, than those closer to the extreme. For example the probability that our algorithm is going to return 320 as the number of people that don’t vaccinate their kids is lower (~4% of the answers are going to be around that value) than the probability that the algorithm is going to return a value around 500 as the answers (~92%).Eve cannot devise an attack that will give her the exact number of people that are not vaccinating their children, and she cannot interfere the answer either by repeatedly asking the question and creating some kind of mean or median value.

Considering the amount of data that we are producing and sharing every moment data privacy and security is one of the most researched fields at the moment. Differential privacy is offering a balance between the utility of the data and the privacy of the user that is being embraced by more and more companies. Data privacy offers all of us a chance to make research collaboration easier and safer for everyone.

References:

Arvind Narayanan, Vitaly Shmatikov, Robust De-anonymization of Large Datasets

Cynthia Dwork, Aaron Roth, The Algorithmic Foundations of Differential Privacy

This work has been published in the ACM XRDS magazine, the Spring 2018 issue.

Let me know what you think!