k-Anonymity and cluster based methods for privacy 22 Apr 2017

Society is experiencing exponential growth in the number and variety of data collections containing person-specific information. This data has been collected both by governments and by private entities. Data and knowledge extracted by data mining techniques represent a key asset to the society, giving information about trends and patterns, helping formulate public poliicies. Ideally, we would want that our personal data to be off the internet, but laws and regulations require that some collected data must be made public, for example census data. Besides that there is a lot of data out there about each one of us over which we don’t have any power of decision. Health-care datasets might be made public for clinical studies, or just because that’s the policy of the state where you are living, to make public the hospital discharge database. There is a new trend to find out your ancestry by buying one of those DYI at home kits, so there are huge genetic datasets, see 23andme, HapMap, where your data is stored and a company owns it. Demographic datasets can offer a lot of information as well, the U.S. Census Bureau or any sociology study that you took part in might make that data public and let the entire world know intimate aspects of your person. And let’s not forget about all the data collected by searching engines, social networks, Amazon, Netflix.

Looking at the list of all the places where you left your personal data you might think that the whole world has it. And this information is valuable, both in research and bussiness. At the same time data sharing is common. But, publishing the data may put your privacy at risk. So what’s the end goal? Maximize data utility while limiting disclosure risk to an acceptable level, where acceptable level will be defined on a case by case situation.

So we need a form of privacy. What is privacy? Privacy is the protection of an individual’s personal information. Privacy is the rights and obligations of individuals and organizations with respect to the collection, use, retention, disclosure and disposal of personal information. But, privacy is not confidentiality. So there was a need to find a way to share data while the privacy of the individual user was preserved.

At the beginning of 2000s there was a famous case of data privacy breaching. Latanya Sweeney detailed the case in his paper. Group Insurance Commissions - GIC, Massachusetts - collected patient data for ~135,000 state employees. Gave this data to researchers and sold it to industry. An attack was performed on the data and the medical record of the former state governor is identified. The attack is called re-identification by linking. Having the medical data and a voter registration database, the individuals can be re-identified by using a small number of attributes called Quasi-identifiers.

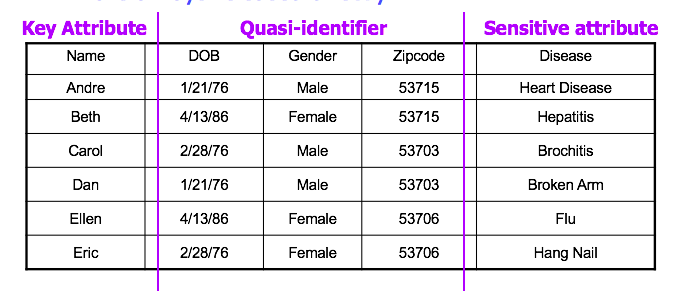

So what are Quasi-identifiers? The 5-digit ZIP code, birth date, gender form a quasi-identifier and uniquely identify 87% of the population in the U.S. Can be used for linking anonymized dataset with other datasets. Quasi-identifiers differ from key-attributes, which are name, address, phone number, that are always removed before releasing the data. There’s a third category of attributes - sensitive attributes. Those are medical records, salaries the attributes that researchers need, so they are always released directly.

k-Anonymity protection model

The intuition behind the k-Anonymity protection model is that the information for each person contained in the released table cannot be distinguished from at least k-1 individuals whose information also appears in the release. Example: you try to identify a man in the released table, but the only information you have is his birth date and gender. There are k men in the table with the same birth date and gender. So to be able not to use re-identification while we use k-Anonymity any quasi-identifier present in the released table must appear in at least k records.

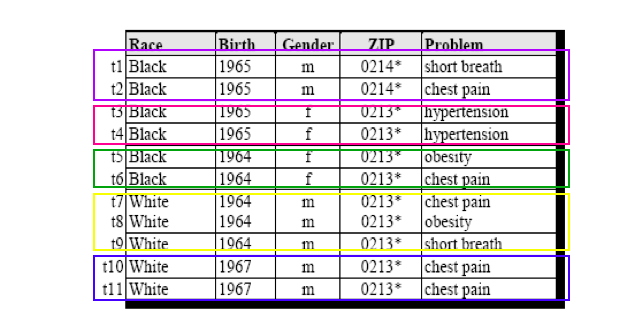

The goal of k-Anonymity is that each record is indistinguishable from at least k-1 other records and these k records form an equivalence class. The idea behind k-anonymity is to make it hard to link sensitive and insensitive attributes. Rows ae “clustered” (partitioned) into sets of size at least k. To achive k-Anonymity there are two main ways to do it:

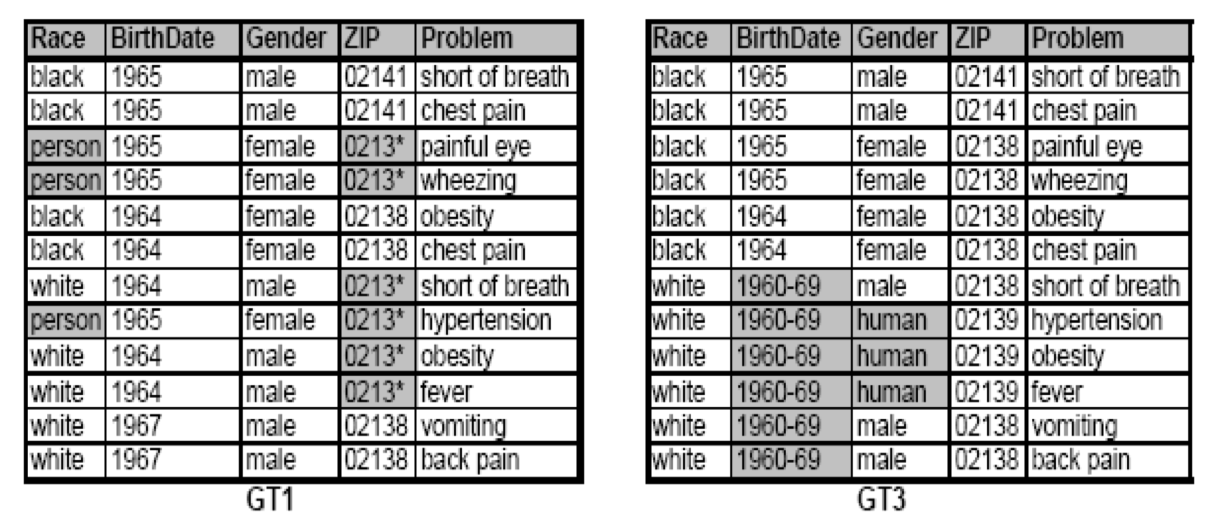

- Generalization : replace quasi-identifiers with less specific, but semantically consistent values until get k identical values and partition ordered-value domains into intervals.

- Suppression : when generalization causes too much information loss then the quasi-identifier is omitted, not released at all. This is common with outliers.

Below is an example of a k-Anonimity table with k=2 and the quasi-identifiers = {birth, gender, race, zip}

So how does generalization work? For example if we have the two tables presented in the figure below, one table is the released data and has as quasi-identifiers the same attributes as the previous table: burth, gender, race, and zip, and releases the health issues that the researchers are interested in. The other table is unrelated to this data release, is an external table, might be voter registration data. So by linking the two tables, the release data sanitized by applying generalization - and the voter registration table we still can’t learn Andre’s health problem.

So the generalization technique fundamentally relies on spatial locality as in each record must have k close neighbors. But, real-world datasets are very sparse, they have many attributes - dimensions - if we look at Amazon customer records each record has several million dimensions. So the “nearest neighbor” is very far. This means that projection to low dimensions loses all info, so k-anonymized datasets are useless. This is called the curse of dimensionality.

Attacks on k-Anonymity

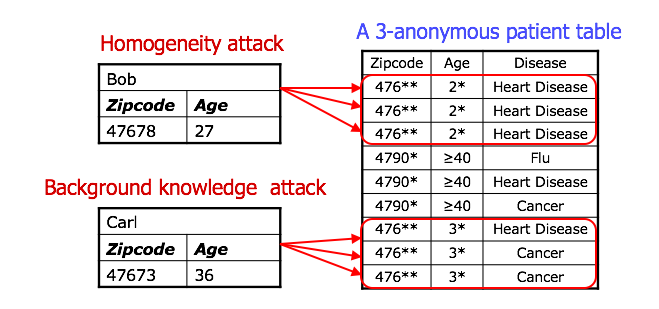

Still, it might look like k-Anonymity is offering us the desired protection, right? Right? The truth is the method is vulnerable to many attacks. Besides the fact that it doesn’t have a mathematical guarantee, it is vulnerable to:

1.unsorted matching attack : the problem is that records appear in the same order in the released table as in the original table. The solution for this is simple, randomize order before releasing

- complementary release attack : different releases of the same private table can be linked together to compromise k-anonymity

So k-Anonymity does not provide privacy if sensitive values in an equivalence class lack diversity or the attacker has background knowledge. So it’s a very weak privacy guarantee.

l-diversity model

l-diversity is an extension of the k-anonymity model and adds the promotion of intra-group diversity for sensitive values in the anonymization mechanism. What that measns is that l-diversity preserves privacy in data sets by reducing the granularity of a data representation.

A formal definition of the l-diversity model is: an equivalence class is said to have l-diversity if there are at least l “well represented” values for the sensitive attribute. A table is said to have l-diversity if every equivalence class of the table has l-diversity. This method still doesn’t prevent probabilistic inference attacks.

Attacks on l-diversity

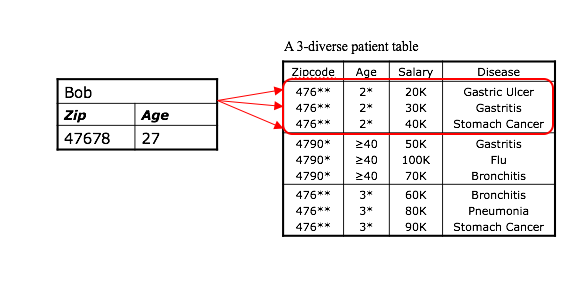

l-divesity is vulnerable to different attacks, one of them being the similarity attack. For example, consider a data release from a hospital that is k-anonymous and l-diverse. An attacker could interfer that Bob is a patient present in that data release and, moreover, it could find out that Bob’s salary is between [20k, 40k], relatively low, and that he has a stomach-related disease. This is a good example for l-diversity not considering semantic meanings of sensitive data.

Composition Attacks

Consider the scenario that several servers with overlapping users (e.g. hospitals that serve overlapping population) independently release “anonymized” statistics on their data. Somewhat surprisingly, we are able to derive much information combining these independent releases, even if k-anonymity (or its variant) has been applied for each statistic. This is because of two crucial properties of k-anonymity and in general of partition-based schemes: • Exact disclosure: the sensitive lists are untouched. This feature is nearly universal. • Locatability: with big chance we can find Alice’s groups given non-sensitive attributes.

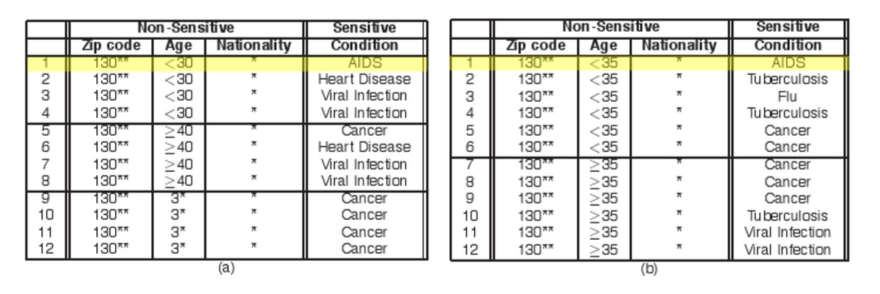

As a concrete example, suppose two hospitals output the two tables below with 4- and 6- anonymity applied on their data, respectively. Now if Alice’s employer knows that she is 28 years old and lives in zip 13012 and visited both hospitals, it is easy to conclude that Alice has AIDS by combining the two releases.

The following equation gives us a sense why composition attacks are feasible. First we need to make some assumptions. Suppose we have two datasets 1 and 2 with the following simplified features: • There is one person, say Alice, in overlap, and Alice has the same sensitive value in both datasets. • Alice is grouped with (k − 1) other people in each of the 2 datasets. • Sensitive attributes are chosen independently and uniformly from a set of size t, say [t] = {1, …, t} • Partitioning depends only on insensitive values.

We are interested in the number of sensitive values that are overlapping (appearing in both sets). Let S1 be the set of sensitive values in dataset 1; S2 be the set of sensitive values in dataset 2. Then

Pr(|S1 ∩ S2|>1) ≤( k−1)^2/tThis shows that smaller k and larger t will make it less likely to identify Alice, and vice versa.

Conclusion

As we have seen the notion of privacy under k-anonymity and its variants is vulnerable, especially under composition attacks. A mathematical proof definition of privacy will be presented in a future post: differential privacy.